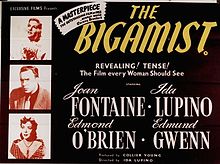

Among the handful of films directed by actress Ida Lupino is the 1953 drama The Bigamist, notable among her works as the only film which she both directed and co-starred in. Lupino is joined by Joan Fontaine, Edmund Gwenn, and Edmond O’Brien in this well-made and well-acted 78 minute movie, which belies its melodramatic title by offering an often refreshingly subtle portrayal of one man and his two marriages (paradoxical as that sounds).

Among the handful of films directed by actress Ida Lupino is the 1953 drama The Bigamist, notable among her works as the only film which she both directed and co-starred in. Lupino is joined by Joan Fontaine, Edmund Gwenn, and Edmond O’Brien in this well-made and well-acted 78 minute movie, which belies its melodramatic title by offering an often refreshingly subtle portrayal of one man and his two marriages (paradoxical as that sounds).

The story begins as married couple Harry and Eve Graham (O’Brien and Fontaine) visit an adoption agency run by Mr. Jordan (Gwenn) in their Los Angeles home base. After eight years of marriage and many visits to the doctor, they have discovered that Eve cannot have any children, and so are seeking to obtain a child in another way. Mr. Jordan is highly concerned with the question of couples’ suitability to become adoptive parents, and asks the Grahams to sign forms allowing him to do a thorough background check on both of them. Eve signs happily, but Jordan, noting Harry’s extreme reluctance, guesses that something is amiss and engages in a determined search, ended by his discovery of Harry in a neat little house in San Francisco, with a crying baby in the back room.

Much of the rest of the film is narrated in flashback, as the distraught Harry tells Jordan about the circumstances that led to his bigamous marriage to Phyllis Martin (Lupino), a San Francisco waitress he met during one of his long and lonely business sojourns away from his home and his wife. Perhaps the most emotionally convincing part of the movie, in fact, is the presentation of Harry’s loneliness, both on his business trips and at home with his somewhat remote, business-minded wife. Harry and Eve have started a company that sells freezers (an apt metaphor, perhaps, for the emotional alienation of several of the movie’s characters) and Harry works as a travelling salesman for the concern, while Eve manages the office end. This is facilitated by their childless state, but makes no provisions for Harry’s emotional needs, and his attraction to Phyllis is partly fueled by her own loneliness and her need for him, as opposed to Eve’s apparent self-sufficiency. Harry’s romance with Phyllis is tastefully, sometimes elliptically presented, and Lupino does a very fine job of creating a believable, likeable girl whose assumption of toughness actually masks a deep vulnerability.

While the film’s plot trajectory is easy to guess, the details of characterization and acting along the way lift the movie from the rank of mere melodrama to the more rewarding category of character study. O’Brien is a fine choice for the role of Harry Graham–his middle-age, his quality of Everyman, both add to the believability of the loneliness and essential decency which lead him to deceive two women at once. The film gives us enough information on both Phyllis and Eve to let us realize that Harry can, and in fact does, love both of them. And as Jordan states at the conclusion of Harry’s narrative, Harry himself inspires a strange kind of sympathy despite his less than clear-headed actions. It isn’t hard to see why The Bigamist is often listed as a noir, for the voice-over narration, the city setting, the atmosphere of secrets and deception, the dramatic ironies, the loneliness, and the complexity of human motives and emotions all echo the preoccupations of more canonical noir. But Harry himself recalls Scobie, hero of Graham Greene’s classic 1948 novel The Heart of the Matter, whose deep pity for all living creatures leads him to create a similarly tangled and unsatisfactory situation involving both his wife and a lonely young widow. Like Scobie, Harry’s desire to do the right thing and ensure the happiness and security of two women leads to disaster for all, showing the cruelties of fate and the difficulties of human control over any events involving other people.

The film’s ambiguous conclusion adds to its tensions by leaving the audience to determine the ultimate meaning of a few looks between the three protagonists, and also by removing the three leads from the sphere of private life and private emotion to the public, communal space of the courtroom and the law. While the emotional impact of the film initially appears to suffer from this, however, the juxtaposition of the leads with each other, while so much of the film depended on their being separate, adds a sense of their plight’s urgency and gravity. Still, the moral teachings voiced by the judge take something away (by their explicit, didactic nature) from the film’s impact upon the viewer, although it does bring to the fore the gulf between sin and social sin, as the judge acknowledges when he points out that Harry’s relationship with Phyllis would have been condoned if it had remained on the level of dalliance–what damned Harry was his desire to do the right thing, another example of the dramatic irony that fills the film.

Another interesting aspect of the movie is its treatment of the theme of children and how acutely (perhaps even excessively) both women feel either their inability to have children or their inconvenient promptitude in having one. While Eve admits that her bitterness at her infertility caused her to turn away from her wifely role in order to concentrate on their business, Phyllis tries valiantly to take full responsibility for her state and later even speaks of her marriage in self-reproachful terms, as though she alone had anything to do with its bringing about. Both women are responsible, ultimately mature people, not the clinging parasitical sort of woman O’Brien might have been tempted to treat more lightly, thus rendering his dilemma less morally compelling. It’s to the credit of all three leads that they make The Bigamist a memorable and complex picture which lingers in the mind long after its final reel has unrolled.